February 16, 2010 | 2119 GMT

By Kamran Bokhari, Peter Zeihan and Nathan Hughes

On Feb. 13, some 6,000 U.S. Marines, soldiers and Afghan National Army (ANA) troops launched a sustained assault on the town of Marjah in Helmand province. Until this latest offensive, the U.S. and NATO effort in Afghanistan had been constrained by other considerations, most notably Iraq. Western forces viewed the Afghan conflict as a matter of holding the line or pursuing targets of opportunity. But now, armed with larger forces and a new strategy, the war — the real war — has begun. The most recent offensive — dubbed Operation Moshtarak (“Moshtarak” is Dari for “together”) — is the largest joint U.S.-NATO-Afghan operation in history. It also is the first major offensive conducted by the first units deployed as part of the surge of 30,000 troops promised by U.S. President Barack Obama.

The United States originally entered Afghanistan in the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks. In those days of fear and fury, American goals could be simply stated: A non-state actor — al Qaeda — had attacked the American homeland and needed to be destroyed. Al Qaeda was based in Afghanistan at the invitation of a near-state actor — the Taliban, which at the time were Afghanistan’s de facto governing force. Since the Taliban were unwilling to hand al Qaeda over, the United States attacked. By the end of the year, al Qaeda had relocated to neighboring Pakistan and the Taliban retreated into the arid, mountainous countryside in their southern heartland and began waging a guerrilla conflict. In time, American attention became split between searching for al Qaeda and clashing with the Taliban over control of Afghanistan.

But from the earliest days following 9/11, the White House was eyeing Iraq, and with the Taliban having largely declined combat in the initial invasion, the path seemed clear. The U.S. military and diplomatic focus was shifted, and as the years wore on, the conflict absorbed more and more U.S. troops, even as other issues — a resurgent Russia and a defiant Iran — began to demand American attention. All of this and more consumed American bandwidth, and the Afghan conflict melted into the background. The United States maintained its Afghan force in what could accurately be described as a holding action as the bulk of its forces operated elsewhere. That has more or less been the state of affairs for eight years.

That has changed with the series of offensive operations that most recently culminated at Marjah.

Why Marjah? The key is the geography of Afghanistan and the nature of the conflict itself. Most of Afghanistan is custom-made for a guerrilla war. Much of the country is mountainous, encouraging local identities and militias, as well as complicating the task of any foreign military force. The country’s aridity discourages dense population centers, making it very easy for irregular combatants to melt into the countryside. Afghanistan lacks navigable rivers or ports, drastically reducing the region’s likelihood of developing commerce. No commerce to tax means fewer resources to fund a meaningful government or military and encourages the smuggling of every good imaginable — and that smuggling provides the perfect funding for guerrillas.

Rooting out insurgents is no simple task. It requires three things:

- Massively superior numbers so that occupiers can limit the zones to which the insurgents have easy access.

- The support of the locals in order to limit the places that the guerillas can disappear into.

- Superior intelligence so that the fight can be consistently taken to the insurgents rather than vice versa.

Without those three things — and American-led forces in Afghanistan lack all three — the insurgents can simply take the fight to the occupiers, retreat to rearm and regroup and return again shortly thereafter.

But the insurgents hardly hold all the cards. Guerrilla forces are by their very nature irregular. Their capacity to organize and strike is quite limited, and while they can turn a region into a hellish morass for an opponent, they have great difficulty holding territory — particularly territory that a regular force chooses to contest. Should they mass into a force that could achieve a major battlefield victory, a regular force — which is by definition better-funded, -trained, -organized and -armed — will almost always smash the irregulars. As such, the default guerrilla tactic is to attrit and harass the occupier into giving up and going home. The guerrillas always decline combat in the face of a superior military force only to come back and fight at a time and place of their choosing. Time is always on the guerrilla’s side if the regular force is not a local one.

But while the guerrillas don’t require basing locations that are as large or as formalized as those required by regular forces, they are still bound by basic economics. They need resources — money, men and weapons — to operate. The larger these locations are, the better economies of scale they can achieve and the more effectively they can fight their war.

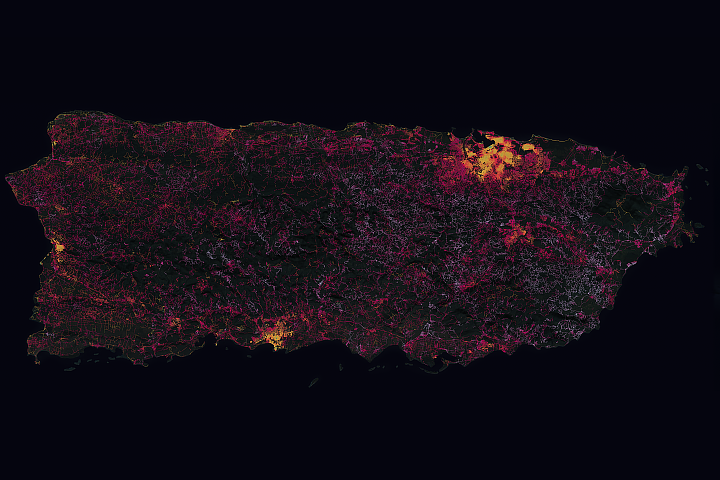

Marjah is perhaps the quintessential example of a good location from which to base. It is in a region sympathetic to the Taliban; Helmand province is part of the Taliban’s heartland. Marjah is very close to Kandahar, Afghanistan’s second city, the religious center of the local brand of Islam, the birthplace of the Taliban, and due to the presence of American forces, an excellent target. Helmand alone produces more heroin than any country on the planet, and Marjah is at the center of that trade. By some estimates, this center alone supplies the Taliban with a monthly income of $200,000. And it is defensible: The farmland is crisscrossed with irrigation canals and dotted with mud-brick compounds — and, given time to prepare, a veritable plague of IEDs.

Simply put, regardless of the Taliban’s strategic or tactical goals, Marjah is a critical node in their operations.

The American Strategy

Though operations have approached Marjah in the past, it has not been something NATO’s International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) ever has tried to hold. The British, Canadian and Danish troops holding the line in the country’s restive south had their hands full enough. Despite Marjah’s importance to the Taliban, ISAF forces were too few to engage the Taliban everywhere (and they remain as such). But American priorities started changing about two years ago. The surge of forces into Iraq changed the position of many a player in the country. Those changes allowed a reshaping of the Iraq conflict that laid the groundwork for the current “stability” and American withdrawal. At the same time, the Taliban began to resurge in a big way. Since then the Bush and then Obama administrations inched toward applying a similar strategy to Afghanistan, a strategy that focuses less on battlefield success and more on altering the parameters of the country itself.

As the Obama administration’s strategy has begun to take shape, it has started thinking about endgames. A decades-long occupation and pacification of Afghanistan is simply not in the cards. A withdrawal is, but only a withdrawal where the security free-for-all that allowed al Qaeda to thrive will not return. And this is where Marjah comes in.

Denying the Taliban control of poppy farming communities like Marjah and the key population centers along the Helmand River Valley — and areas like them around the country — is the first goal of the American strategy. The fewer key population centers the Taliban can count on, the more dispersed — and militarily inefficient — their forces will be. This will hardly destroy the Taliban, but destruction isn’t the goal. The Taliban are not simply a militant Islamist force. At times they are a flag of convenience for businessmen or thugs; they can even be, simply, the least-bad alternative for villagers desperate for basic security and civil services. In many parts of Afghanistan, the Taliban are not only pervasive but also the sole option for governance and civil authority.

So destruction of what is in essence part of the local cultural and political fabric is not an American goal. Instead, the goal is to prevent the Taliban from mounting large-scale operations that could overwhelm any particular location. Remember, the Americans do not wish to pacify Afghanistan; the Americans wish to leave Afghanistan in a form that will not cause the United States severe problems down the road. In effect, achieving the first goal simply aims to shape the ground for a shot at achieving the second.

That second goal is to establish a domestic authority that can stand up to the Taliban in the long run. Most of the surge of forces into Afghanistan is not designed to battle the Taliban now but to secure the population and train the Afghan security forces to battle the Taliban later. To do this, the Taliban must be weak enough in a formal military sense to be unable to launch massive or coordinated attacks. Capturing key population centers along the Helmand River Valley is the first step in a strategy designed to create the breathing room necessary to create a replacement force, preferably a replacement force that provides Afghans with a viable alternative to the Taliban.

That is no small task. In recent years, in places where the official government has been corrupt, inept or defunct, the Taliban have in many cases stepped in to provide basic governance and civil authority. And this is why even the Americans are publicly flirting with holding talks with certain factions of the Taliban in hopes that at least some of the fighters can be dissuaded from battling the Americans (assisting with the first goal) and perhaps even joining the nascent Afghan government (assisting with the second).

The bottom line is that this battle does not mark the turning of the tide of the war. Instead, it is part of the application of a new strategy that accurately takes into account Afghanistan’s geography and all the weaknesses and challenges that geography poses. Marjah marks the first time the United States has applied a plan not to hold the line, but actually to reshape the country. We are not saying that the strategy will bear fruit. Afghanistan is a corrupt mess populated by citizens who are far more comfortable thinking and acting locally and tribally than nationally. In such a place indigenous guerrillas will always hold the advantage. No one has ever attempted this sort of national restructuring in Afghanistan, and the Americans are attempting to do so in a short period on a shoestring budget.

At the time of this writing, this first step appears to be going well for American-NATO-Afghan forces. Casualties have been light and most of Marjah already has been secured. But do not read this as a massive battlefield success. The assault required weeks of obvious preparation, and very few Taliban fighters chose to remain and contest the territory against the more numerous and better armed attackers. The American challenge lies not so much in assaulting or capturing Marjah but in continuing to deny it to the Taliban. If the Americans cannot actually hold places like Marjah, then they are simply engaging in an exhausting and reactive strategy of chasing a dispersed and mobile target.

A “government-in-a-box” of civilian administrators is already poised to move into Marjah to step into the vacuum left by the Taliban. We obviously have major doubts about how effective this box government can be at building up civil authority in a town that has been governed by the Taliban for most of the last decade. Yet what happens in Marjah and places like it in the coming months will be the foundation upon which the success or failure of this effort will be built. But assessing that process is simply impossible, because the only measure that matters cannot be judged until the Afghans are left to themselves.

Tell STRATFOR What You Think | Read What Others Think |

Reprinting or republication of this report on websites is authorized by prominently displaying the following sentence at the beginning or end of the report, including the hyperlink to STRATFOR:

"This report is republished with permission of STRATFOR"