Tragédia similar a de Pinheiros, 20 anos atrás. Mas, atentem para o laudo do IPT à época...

Thursday, January 18, 2007

Felizes Trópicos 2

Tragédia similar a de Pinheiros, 20 anos atrás. Mas, atentem para o laudo do IPT à época...

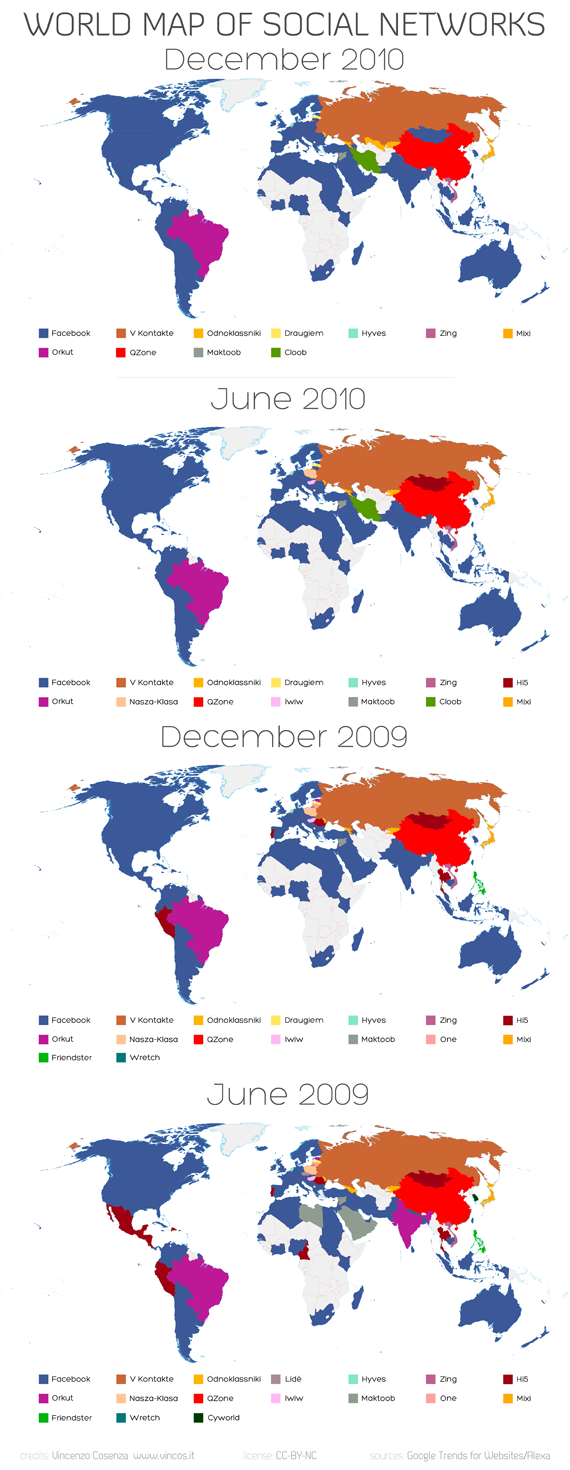

Migrações no mundo ex-comunista

Migration

Europe's huddled masses

Jan 18th 2007

From The Economist print edition

Millions of Europeans are on the move. Does it matter?

ROBERT, the Polish-born head of a group of British removal men, can read and write English easily, unlike his British colleagues who after packing their cardboard boxes label them as “clovs” and “shuse”. Two years ago, when he moved to Britain, Robert lugged heavy loads like them. He still lives worse than they do, in a shabby rented house crammed with compatriots. But the remittances he sends home are paying for his family, a car, a house and—eventually—his own business there.

That dream, of hard work abroad leading to success at home, has inspired millions of people to move across Europe since the collapse of communism—a peacetime migration exceeded only by the upheavals that followed the end of the second world war. But remarkably little is known about the nature of this movement of people one way, and money the other, not least because so much is undocumented or illegal. Now a new report* from the World Bank attempts to fill some gaps and explode some misconceptions.

The first is that the main migration is from the ex-communist world to what used to be called the West, when in fact Russia is the main destination for immigrants, surpassed only by America. That is due partly to ethnic Russians returning to the motherland after the break-up of the Soviet Union, but also to Tajiks, Georgians, Moldovans and other non-Slav citizens of ex-Soviet republics moving to Russia in search of work. In the process, Georgia, for example, lost a fifth of its population in the 14 years from 1989.

The money-flows from migration—around $19 billion annually, the authors estimate—are surprising too. In some countries they matter more than foreign investment. For example, remittances make up more than a quarter of Moldova's GDP—a figure exceeded worldwide only in Haiti and Tonga. For nine ex-communist countries, remittances provide 5% or more of national income. In the region as a whole, three-quarters of the money comes from migrants working in the European Union; about a tenth from those in the former Soviet Union.

The big question is the impact on the home country's development. Optimists think that remittances prop up current accounts and help development. “Whereas aid to governments is often wasted or siphoned off into Swiss bank accounts, migrants' remittances end up directly in poor people's pockets,” says Philippe Legrain (formerly of The Economist) in a book† arguing the case for migration.

But pessimists reckon that having the best and brightest working abroad, often in menial jobs, is a dreadful loss. Remittances may also keep currencies artificially high, harming growth. The World Bank's authors think only a third of remittances go on education, savings and business investment. The overall result, they surmise, has been a mild stimulus to growth in the recipient countries, but without a measurable effect on poverty: it is better-off, urban families that tend to send someone abroad, and then reap the benefits.

The final misconception is about what motivates migration. “Everyone thinks it is all about income differentials, but actually it is all about expectations. Even in poor countries we can expect low levels of migration if people think that conditions there will improve,” argues Brice Quillin, one of the report's authors.

From one viewpoint, the huge migration of recent years to western Europe seems unlikely to continue. Populations are declining in all countries (except Albania) in the western half of the post-communist region. That tightens their labour markets and may stimulate migration from farther east. By contrast, populations in the southern states of the former Soviet Union—countries such as Tajikistan—will keep growing until the middle of this century. “If the typical migrant of the 1990s was a Pole moving to Britain, his successor in the next decade may be a Tajik moving to Poland,” says Mr Quillin. Even Turkey, previously a big exporter of workers, now imports migrants.

From one viewpoint, the huge migration of recent years to western Europe seems unlikely to continue. Populations are declining in all countries (except Albania) in the western half of the post-communist region. That tightens their labour markets and may stimulate migration from farther east. By contrast, populations in the southern states of the former Soviet Union—countries such as Tajikistan—will keep growing until the middle of this century. “If the typical migrant of the 1990s was a Pole moving to Britain, his successor in the next decade may be a Tajik moving to Poland,” says Mr Quillin. Even Turkey, previously a big exporter of workers, now imports migrants.What really helps putative migrants stay at home is not just higher wages but the prospect of fast, effective reform, bringing better public services and a dependable legal system. Employers in post-communist countries, particularly those outside big cities with a local monopoly in the job market, still treat their employees with remarkable casualness. A sawmill in a small town, for example, may fail to pay wages, and then declare bankruptcy, only to restart under a new name with the same owners, managers and workforce.

The catch is that reform throughout the region is flagging. No country between the Baltic, Black and Adriatic seas can boast a strong reformist government, and with a few exceptions the farther east you go, the worse it gets.

.

.

Desperdício de água na cidade da "qualidade de vida"

Em Ribeirão da Ilha, na Ilha de Santa Catarina, parte integrante do município de Florianópolis/SC, o aposentado Alberto Jorge da Silva de 47 anos perdeu sua plantação de cana-de-açúcar devido a um vazamento de água da Casan, a distribuidora de água. A causa: uma válvula estragada. Se faz campanha para economizar água tratada, se combate, publicitariamente, o desperdício incentivando os consumidores a encurtarem o período do banho etc., mas o excesso d'água em sua várzea já dura cinco anos![1]

E a companhia de saneamento e águas da capital – CASAN – perde 40% da arrecadação devido a fraudes, os chamados “gatos”. Some a isto os vazamentos que não são, durante meses ou até anos, consertados. Mas, parece que as fraudes são o fator que mais pesa. Chegam a ser 50 ocorrências mensais de adulterações nos hidrômetros. Dificuldades de acesso pelos fiscais, particularmente em áreas violentas e a venda de água a terceiros são comuns.[2]

Culpar só o governo pelo descaso não é justo. A prefeitura de São José, cidade vizinha a Florianópolis, está limpando o Rio Araújo. Máquinas retroescavadeiras foram utilizadas para limpar e desobstruir a tubulação de drenagem. Até agora já foram retirados entulhos em 50 caminhões (!), com todo o tipo de tralha que se pode imaginar: pneus, sofás velhos, madeira, geladeiras, fogões e vasos sanitários.[3] Daí, a população não tem direito nenhum a reclamar pela nova canalização do rio, pois ela própria é porca.

[1] Hora de Santa Catarina, 17 de janeiro de 07.

[2] Notícias do Dia, 19 de janeiro de 2007.

[3] Idem.

Wednesday, January 17, 2007

Este é o verdadeiro movimento que deve se espalhar pela América Latina

11/12/2006 - 22h22

Quatro regiões bolivianas aceleram processo de autonomia

da Folha Online

Tuesday, January 16, 2007

De BRIC para brick

No ano passado, a ONU projetou crescimento global de 3,6%. Só o leste asiático era estimado em mais de 7% e, mesmo para uma burocratizada Comunidade dos Estados Independentes (CEI), se esperava mais de 6%. A Europa, ainda carregando o peso de seus welfare states, beirava os 3%. É mais difícil para “economias maiores” darem mostras de flexibilidade superiores que a de países emergentes, o que explica, em parte, a pequena taxa européia.

Tais projeções parecem corroborar o “fim da História” de Fukuyama. O capitalismo veio para ficar, apesar de capengar conforme a região. Então, para que tanta celeuma sobre “um outro mundo possível” do Fórum Social Mundial?

Não adianta, sempre teremos descontentes com a globalização ou o velho e bom capitalismo. Quem pensa que tais questões são exclusivas da “esquerda” se engana. Há quem ache que o comunismo ainda não morreu e que a ONU faz parte de uma conspiração mundial para alicerçá-lo em novas bases. Claro que se pode discutir que o capitalismo global não é liberal o suficiente e que os conluios entre transnacionais e estados nacionais implicam em uma nova forma de despotismo econômico. Despotismo enfim. Ou tudo isto é um jogo em que nos enganam ou as visões conspiratórias não se sustentam.[1]

Se for verdade que 70% dos produtos vendidos no Wal-Mart são de procedência chinesa, o capitalismo vige e vinga ou é usado pelas velhas ditaduras comunistas que se reciclam? Não creio em permanência na História. Não tenho conhecimento de nenhuma classe econômica que ampliasse seu poder sem almejar (e conquistar) o poder político igualmente. Assim, em Pequim aguardo por transformações democráticas. Posso ser ingênuo ou incuravelmente otimista, mas o estado chinês irá mudar.

Mais que oposições diplomáticas entre China e EUA, os dois países aprofundam uma salutar dependência. A reciprocidade no comércio externo e nos influxos de capital é benfazeja, pois quando crescem, diminui o potencial de conflito.

A sinergia econômica parece que vai ser acompanhada pela política. Com a mudança do secretário de Defesa dos EUA que trocou Donald Rumsfeld (2001-2006) para Robert Gates, finda o breve período neocon[2], cuja pedra de toque idealista era o “ataque preventivo”. O realismo político que deverá ser a tônica com esta nova administração não é nada novo. Permeou a maior parte da política externa norte-americana e, apesar de seus inúmeros erros, como apoiar ditaduras latino-americanas, trouxe mais benefícios do que as desbaratadas ações preventivas que, na retórica pretendiam disseminar o vírus da democracia em regiões tribais do globo. Os neoconservadores ingenuamente acreditam que ações externas intervencionistas, dirigidas a mudanças de regimes, criariam um mundo melhor e mais pacífico.[3]

Política para quem domina não se move por ideologia, mas justamente por necessidade e senso de oportunismo mesmo. México, Índia, Brasil e União Européia não são ambíguos quando se aproximam dos EUA. Só executam os mesmos princípios que tonalizam a própria política deste país no seu comércio externo. Dizer que a opinião dominante na mídia e instituições culturais é maciçamente antiamericana não reflete o que os governos em suas “razões de estado” definitivamente fazem.

E é a própria burocracia chinesa que está influindo em sua economia ao definir 39 princípios básicos que diminuem o peso do estado e a encaminham em direção do setor privado, objetivando utilizar os preços de mercado tanto quanto possível. Teoricamente, as bases para a democratização da sociedade no futuro estão sendo sedimentadas. Recente estudo da consultoria McKinsey evidencia a redução da pobreza chinesa de 77,3%, em 2005, para 9,7% em 2025, a continuar o atual ritmo de crescimento.[4]

A China de hoje, não é mais apenas um “mercado”. É um mundo a parte que toma as rédeas de seu próprio destino. Acabou de ultrapassar o próprio Japão, em gastos em pesquisas científicas e tecnológicas. Sim, estou me referindo aquele Japão, campeão em inovações tecnológicas. Os gastos chineses foram de USD 136 bilhões no ano passado, seis a mais que seu vizinho insular.

Quando pensamos em reformas no Brasil (que não saem) não deixa de ser triste a conclusão de que um forte desincentivo parte, justamente, do aumento dos preços das commodities no mercado internacional devido ao aumento do consumo chinês e indiano. Diferente do gigante asiático, nosso gigante (“de pés de barro”, nunca é demais lembrar...) surfa em uma inativa postura diante das ondas globais definidas por outros países. Isto somado a derrubada de barreiras comerciais aos produtos brasileiros nos EUA que por mais de uma década vigoraram, aponta para uma lei física de nossa economia: a inércia, pois o que China ou EUA vierem a executar, nos bastará.

Falar em globalização nestes “bobos trópicos” parece significar apenas redução de tarifas alfandegárias que, por si só, acaba aí sem atenção maior ao próprio mercado interno. Apesar da ditadura comunista na China, este país atingiu uma eficácia em seu desempenho econômico muito maior do que o Brasil com sua democracia. A redução das exportações de calçados em 11% em 2005, afetando duramente a Serra Gaúcha, tradicional região produtora, enquanto que o maior produtor mundial hoje em dia, é um gaúcho que atua na China revelam como um ambiente propício influi no desempenho individual. Estamos repletos de batalhadores por aqui, cuja melhor alternativa tem sido o aeroporto.

Obviamente que não vou afirmar que a “democracia econômica é muito mais importante que a democracia política”, mas que uma sem a outra não há sustentabilidade no próprio sistema. Por outro lado, no Brasil vige um pseudo-capitalismo, um “capitalismo de compadrio” em que contribuintes são explorados pelo estamento burocrático. A congênita inércia latino-americana tem a honrosa exceção do Chile que cresceu 4,3% entre 2001 e 2005. Mas, o próprio México, beneficiado pelo NAFTA não faz suas reformas internas e deixa de ser um atrativo para inversões externas. Não é a toa que nosso “grande mercado potencial” (e que sempre é potencial) esteja sob risco de perder posicionamento entre os BRICs – sigla formada pelas iniciais de economias emergentes de Brasil, Rússia, Índia e China: nosso governo cuja “esperança venceu o medo” teve otimismo desproporcionalmente maior do que a competência, como é sabido.

Dizem que nossa sociedade brasileira é “conservadora” ao ser contra o desarmamentismo, contra o casamento gay, contra o aborto, contra as quotas raciais etc. Só esquecem de observar que este mesmo “conservadorismo” também é conservador para a estagnação econômica que vivenciamos, deixando tudo como está ao fornecer salvo conduto para um governo que não prima por reformas e uma estrutura de estado parasitária. Em suma, uma flexibilidade de tijolo.

[1] Segundo a Heritage Foundation, a Estônia, país ex-comunista é hoje o 12º em termos de liberdade econômica; a Lituânia, o 22º e por aí vai...

[2] Rumsfeld e o vice-presidente Richard Cheney não se enquadram bem no rótulo “neo-conservador”. O título é mais adequado para aqueles, como Paul Wolfowitz que consideram os Estados Unidos da América como mais que uma nação, mas uma causa.

[3] Uma das figurinhas mais rasas do novo conservadorismo americano é Ann Coulter, responsável por pérolas do seguinte quilate: “Nós devemos invadir seus países, matar seus líderes e convertê-los ao Cristianismo” (13 de setembro de 2001, itálicos meus e estupidez dela).

[4] Newsletter diária n.º 853 - 08/12/2006 - http://www.amanha.com.br/. Enquanto isto, a projeção é que o Brasil tenha 55 milhões vivendo em favelas em 2020, algo próximo a 25% da população nacional.

Thick as a brick (not smart as a bric)

http://amanha.terra.com.br/

Newsletter diária n.º 871 - 15/01/2007

A expectativa de reformas do governo Lula colocou o Brasil entre os “Brics”

A expectativa de reformas do governo Lula colocou o Brasil entre os “Brics”O Brasil deve perder o posto entre os “Brics”?

Ainda assim, para Fligenspan, nenhum outro país emergente poderia substituir ao “B” da sigla emprestado pelo Brasil. Mesmo com vizinhos como Argentina e Chile crescendo a taxas mais significativas, suas dimensões são muito menores do que a nacional, tornando-as pouco relevantes para compor o quadro desenhado pelos analistas do Goldman Sachs. “Por nossas dimensões continentais, temos um mercado consumidor que nos dá economia de escala para ser um grande competidor mundial”, acrescenta Ardisson Akel, coordenador do Conselho de Comercio Exterior da Federação das Indústrias do Paraná (Fiep). (Eduardo Lorea)

Links relacionados:

Monday, January 15, 2007

Felizes Trópicos

Do contrário, deverá pagar multa diária no valor de R$ 50 mil. Mais fornecimento, no prazo de 48 horas, 38 carros-pipa para atendimento imediato da população do norte fluminense, sob pena de multa diária de R$ 30 mil.

Sunday, January 14, 2007

Chinese accounting

Satoshi Kambayashi

SEPARATING truth from propaganda in China has always been hard, not least when it comes to numbers. Accountants, of all people, were seen as such a threat that during the 1960s they were packed off to re-education camps, dooming the profession for decades afterward. Even in kindlier times, businesses reported information that would interest a centrally planned economy, such as production quotas. The measuring sticks of bourgeois managers—costs, debt, depreciation, and (of course) profit—were ignored.

But since the 1990s China has begun scrubbing up its accounting system. At the beginning of this year it made its biggest move yet when the Ministry of Finance required the 1,200 companies listed on the Shenzhen and Shanghai stockmarkets to adopt, with important exceptions, norms similar to International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). These standards may sound like instruments of accounting torture, but countries all over the world are embracing them. China has given all its other firms the option of complying with them “voluntarily”—a word with many shades of meaning. If the changes are more than just cynical window-dressing designed to attract foreign investment, they will mark a profound shift in what China wants people to know not only about its companies, but also about its economy and its government.

A new accounting system would certainly help China. Most companies are good at keeping tabs on their operations, but the book-keeping is complicated by use of a thick manual that makes bewildering distinctions between different kinds of provisions. The result is a mess. “The records are complete, the question is how do you make sense of them,” says T.J. Wong, a professor of accounting at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Murder by numbers

There is abundant evidence, from trade statistics to fumes spewing out of factories and power plants across the country, that the Chinese economy is doing well. But how well individual companies are doing is far harder to tell. The financial results of companies that global investors wish to buy into can be as unintelligible as the dialect spoken in the company town. It is said (with apparent sincerity) that some Chinese firms keep several sets of books—one for the government, one for company records, one for foreigners and one to report what is actually going on.

Under the new approach, accounts will be prepared under 39 principle-based standards structured to reveal the economic value of a firm, with the aim of using market prices wherever possible. A clear understanding of a firm's revenues, costs and debt would enhance the efficiency of China's companies—the avowed goal—as well as making it easier to attract foreign capital and to invest abroad.

More profoundly, by properly reflecting costs, the heavy burden of state control would become more evident, as would the pricing signals that indicate the real desires of the Chinese people. Sleazy transfers of mispriced assets from the state to the private sector would become vastly more difficult. Theoretically, accounting would serve as a force for democracy.

Given all these benefits, the decision to shift accounting standards was, says one informed observer, not unlike the one to host the Olympics. It emanated from the top of the Beijing government and was aimed at bringing China into line with the rest of the world. Accounting, however, makes Olympiads look easy.

All China must pull off to host the games is to renovate bits of its big cities. By contrast, international accounting standards are built on foundations that China does not possess, such as experience of truthful record-keeping and deep, clean, markets so that “fair” valuations can be placed on financial instruments, property and softer assets like brands and intellectual property. (These in turn rely on enforceable laws.) What market exists that could put a fair price on the clumps of freshly built office blocks that stand empty in cities across China, asks Gary Biddle, a professor of accounting at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

The decision to adopt international accounting standards was made in November 2005, to be put into effect in little more than a year. The announcement generated praise (for its worthy intentions) and shock (for its ambition). America, despite having the world's deepest financial markets, is concerned about using market-based “fair-value” reporting and will only partially converge with international standards by the end of 2008, if then. Thailand and South Korea have yet to pledge convergence of their own systems with IFRS, despite having many years' more experience than China with market-based accounting systems.

Beansprout counters

To witness the scale of the work ahead, you need only look at the upheavals in a mainland firm when it lists its shares in Hong Kong, and must therefore bring its accounts up to international standards. In a developed market, the number-crunching ahead of a listing takes months. In China, it can take up to three years. And these are typically the best Chinese companies, able to afford the best advisors.

Certain conditions, such as “related-party” transactions, are almost impossible to bring into line with international standards, so they will be fudged. Under international accounting norms, deals between companies with overlapping ownership are supposed to be clearly disclosed. This is a sound principle in general and particularly appropriate for companies in countries where the government owns a piece of almost everything, and presses companies to take steps that may be bad for them (such as buying from troubled suppliers to protect jobs).

But because overlapping ownership is so common in China (the government still owns shares in almost every large company), detailing each transaction would overwhelm a financial report. For “pure state-controlled enterprises” there will be no disclosure requirement.

An equally large problem is the lack of accountants to process the raw numbers. In no other place in the world, and probably at no other time in history, have accountants been so sought-after as they are in China. By even the most generous reckoning, the country has fewer than 70,000 practising accountants, trying to do the work of anything from 300,000 to a million bean counters. To be an accounting student at a reputable school is to have a good job waiting. But even after several years of education, accountants require an apprenticeship, especially if they are to get to grips with international standards based on intellectually demanding principles rather prescriptive rules. Accountants in Britain, acknowledging the difficulties, are helping with the training.

Hong Kong and China are also hosting seminars where the new standards are presented to crowds of eager accountants; but the long lectures do not provide anything like enough of a guide to a person preparing, or auditing, a firm's books. It is said that Chinese officials have put pressure on many outsiders helping introduce the new regime to say that convergence has already taken place; that has clearly frightened many, and muffled criticism.

Silence, though, would be costly, says Martin Fahy, director of development for the Asia-Pacific region at the Chartered Institute of Management Accounts. “You can't have a functioning financial market and economy without objective and independent accounting. This is a test for not only China, but for the integrity of the accounting profession as well.”

To gauge accountants' understanding of the changes to financial reporting in China, a manager at a large investment-fund company has asked a string of accounting firms whether earnings will rise or fall or at least better reflect businesses' performance. It is hard to imagine a simpler test. No one had an answer.

.